#167 Keeping Contracting as Simple as Possible

I do not believe enough has been written about what makes a good coaching contract. Over many years of coaching, I have developed my own contracting model, which I outline here.

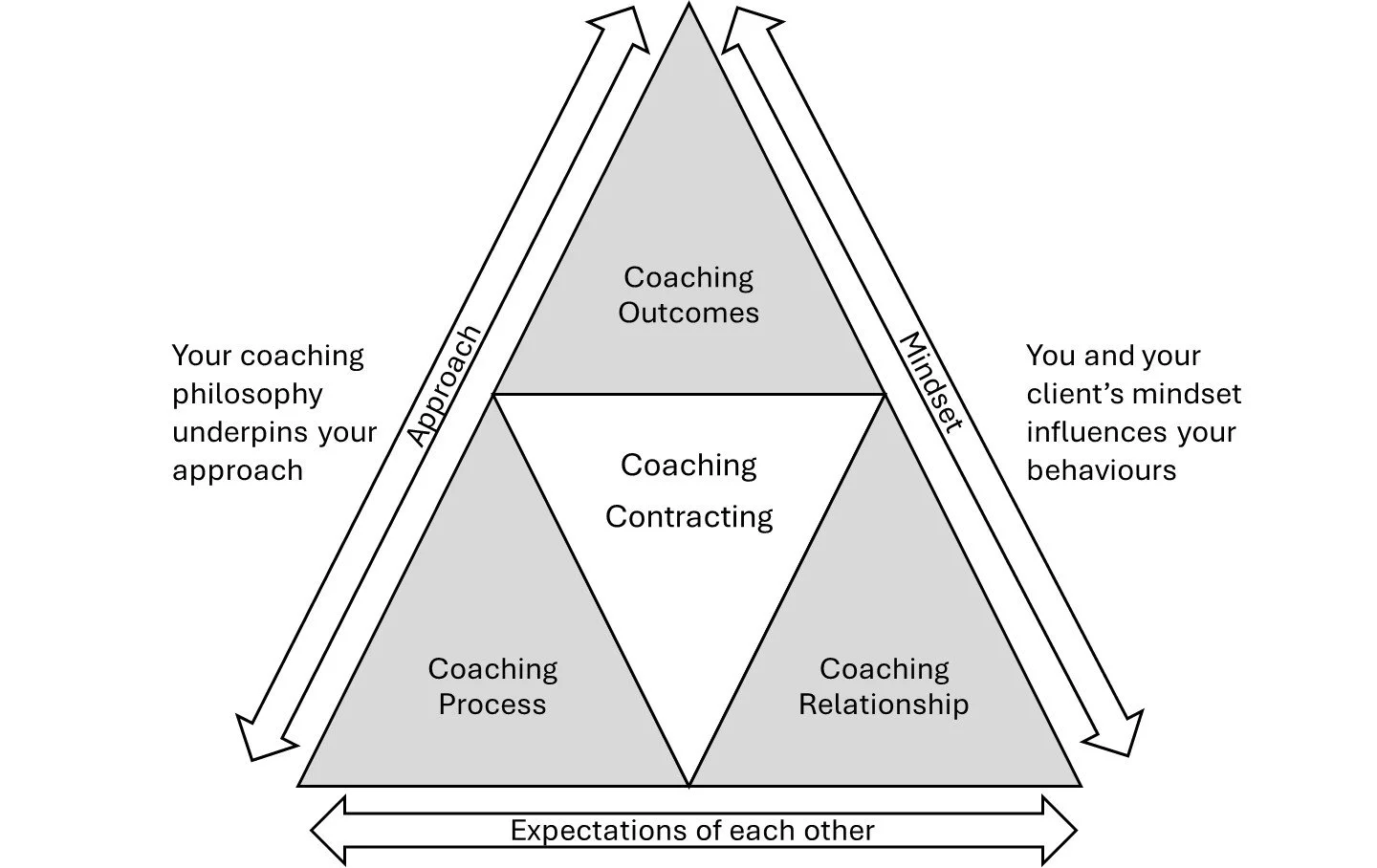

Contracting comprises the verbal agreement I make with my client, which is reinforced with a written agreement. Contracting is about establishing a working alliance before the coaching starts. I like to keep things as simple as possible – and I love working in threes – so, for me, contracting covers coaching goals (outcomes), the boundaries of the coaching engagement (process) and the nature of the coaching relationship. It is also an opportunity to outline who I am as a coach and the expectations my client and I have of each other.

The vast majority of my coaching is conducted without a three-way contract. This is because my clients have often self-selected coaching as part of their career development, or the coaching forms part of a leadership development programme on which they are enrolled. Where this is not the case – eg, performance improvement coaching – I hold a three-way contracting meeting with the client and their coaching sponsor.

Goals (Outcomes)

I agree on coaching goals with my client at the outset of the coaching engagement. I have experimented with SMART (Specific, Measurable, Action-oriented, Realistic, Time-bound) and EXACT (Explicit, eXciting, Assessable, Challenging, Time-framed) at different times throughout my coaching career. I have discovered that, rather than rigidly following such guidelines, a looser, client-centred approach can yield more engagement, although I will nudge clients if I notice their goals are not challenging enough, for example. What is important is that my client’s goals may be aligned with any aspect of their life or work that I am prepared to work with. As my coaching work is predominantly with senior leaders in organisational settings, I often agree performance goals that are known to the sponsor of the coaching, such as my client’s line manager. Following Myles Downey’s ‘public/private’ goal model, these are public goals, and I contract how we will provide feedback to the sponsor on progress against these goals. I sometimes agree on short-term and long-term goals. In addition to public goals, my clients oftentimes want to agree on some private coaching goals, such as developing their self-confidence. I will never agree to provide feedback on progress on such goals to anyone other than my client. See also ‘Confidentiality’ below.

My contracting discussion also includes consideration of how we will measure progress. In cases where there is a three-way contract, I usually include a half-time three-way progress meeting and a three-way review meeting at the conclusion of the coaching programme. I have experimented with formal feedback forms; however, I now tend not to use them, preferring informal evaluation discussions incorporated into the coaching sessions.

Boundaries (Process)

I think about the boundaries of coaching in terms of time, territory and task.

Time (& Place) – I contract for the length of coaching sessions and the duration of the programme. The place we will hold sessions is very important as it may signify the power dynamic in the relationship. I am aiming for equality (see ‘Relationship’ below). The place I hold coaching sessions also acts as a container for the coaching – a safe place to which the client and I return to hold the space and conversation between ourselves. Since Covid, the vast majority of my coaching is undertaken online using Zoom or MS Teams.

Territory – My territory is coaching. Not consulting, giving advice, counselling or taking on the responsibilities of my client (eg, management). ‘Where the coach provides (expert) input, he is reducing the client’s responsibility’, Sir John Whitmore.

Task – I use the contracting meeting to outline my coaching philosophy, process and fees (if not already done at the chemistry stage).

Relationship

The most critical aspect of my coaching contracts is to agree on expectations of each other in terms of roles and responsibilities, confidentiality and equality.

Roles and responsibilities

I contract for what happens if either of us has to cancel a session at varying lengths of notice, eg, when I will charge for a session that is cancelled and when I would be happy to re-arrange it;

I set out the arrangement for termination of the relationship, eg, if the client does not feel they are benefiting, how they can end the coaching and how I will help them find an alternative coach; and

I also cover ethics – I adhere to the Global Code, I am in regular coaching myself, and I engage in professional supervision. I suggest my client may contact my supervisor if they have a complaint or perceive a conflict of interest.

I explicitly set out my position in relation to confidentiality. In my written agreements, this includes signposting my Privacy Policy on my website. See also public and private goals in ‘Goals (Outcomes)’ above.

As a coach, I act in servitude to my client and the system in which they operate. My goal in contracting is to establish a working alliance with them. This means we are equal partners in the relationship. Equality helps to build trust. My written agreement contains both our signatures and a date.

Re-contracting can and will occur throughout the engagement, eg, on goals, time & place, territory and task. I have found I am less likely to re-contract coaching relationships, which is why it is very important I explicitly contract for our expectations of each other at the outset.

In Co-Active Coaching (2011), Henry Kimsey-House et al suggest, ‘The ongoing relationship between coach and client exists only to address the goals of the client’. For me, this demonstrates the mindset I share with my client – an equal working alliance to further their goals.

Good contracting is the first step in flawless coaching

Peter Block’s (2000) ‘Flawless Consulting’ massively influenced my approach to OD consulting, from which my coaching practice emerged. Drawing on his inspiration, I believe coaching flawlessly requires intense concentration on being as authentic as I can be at all times with my client and attending directly, in words and actions, to the business of each stage (beginnings, middles and endings) of the process of coaching. Contracting is a key element of the ‘beginnings’ stage. ‘When [practitioners] talk about their disasters, their conclusion is usually that there was fault in the initial contracting stage’, Peter Block.

My ground rules for contracting, inspired by Block (2000):

The responsibility for every coaching relationship is 50/50. There must be equality or the relationship will collapse.

The contract should be freely entered.

You can’t get something for nothing. There must be consideration from both sides.

All wants are legitimate. To want is a birthright.

You can say no to what others want from you. Even clients.

You don’t always get what you want. And you still keep breathing. You will survive, and you will have more clients in the future.

You can contract for behaviour; you can’t contract for your client to change their feelings.

You can’t ask for something your client doesn’t have. In coaching, we often assume our client has the resources within them to change. How will you test this?

You can’t promise something you don’t have to deliver.

You can’t contract with someone who’s not in the room, such as your client’s bosses. You have to meet with those other people to know you have an agreement with them. Consider three-way contracting where the coaching objectives are predominantly public goals.

Write down contracts when you can. Most are broken out of neglect, not intent.

Social contracts are always renegotiable. If your client wants to renegotiate a contract in midstream, be grateful that they are talking with you about it and not just doing it without a word.

Contracts require specific time deadlines or duration, or - often in coaching – both.

Good contracts require good faith and often accidental good fortune.